Early detection saves lives. Oral cancer is highly treatable when caught in its earliest stages, yet many cases in Nepal are diagnosed late because early signs often cause no pain. Recognizing what to look for, and knowing when to seek professional screening, can make the difference between a simple treatment and a complex, life-altering diagnosis.

This guide walks you through the specific areas to examine, the warning signs that demand attention, and the screening process available in Kathmandu. You will learn the exact steps for a 2-minute self-check, the red flags that require immediate evaluation, and the high-risk conditions that increase your likelihood of developing oral cancer.

Oral cancer: what it is and why early screening matters

Oral cancer can involve the lips, tongue, cheeks, gums, palate, or the floor of the mouth, and early changes may look minor. Many early lesions don’t hurt, so people wait, thinking it will go away. Knowing the common early signs helps you act before a small problem becomes a bigger one.

What “oral cancer” includes (lips, tongue, cheeks, gums, palate, floor of mouth)

Oral cancer refers to malignant tumors that develop in any part of the mouth or oral cavity. This includes the lips, the front two-thirds of the tongue (the part you can stick out), the inner lining of the cheeks, the gums (both upper and lower), the hard palate (roof of the mouth), and the floor of the mouth beneath the tongue.

Each of these areas has different tissue types and different risk profiles. Cancers on the tongue and floor of the mouth tend to be diagnosed later because they sit in less visible locations. Lip cancers, more common in outdoor workers exposed to intense sun, often appear earlier because they are easier to notice. Gum and palate lesions may initially be mistaken for dental problems or denture irritation, delaying proper diagnosis.

Why early oral cancer can be painless (and still serious)

The earliest stages of oral cancer typically produce no pain, numbness, or functional difficulty. This absence of discomfort misleads many people into ignoring a persistent sore, patch, or lump. Pain usually signals that the cancer has grown deeper into nerve-rich tissue or has begun to ulcerate and become infected.

A small white patch (leukoplakia) or red patch (erythroplakia) can sit quietly on your tongue or cheek for weeks without causing any sensation. It gets dark when these silent changes progress unnoticed until they reach a stage where surgical removal becomes extensive and survival rates drop significantly. Early oral cancers confined to the surface layer have cure rates above 80 to 90 percent; late-stage disease with lymph node spread reduces that figure to below 50 percent. Waiting for pain is waiting too long.

Who should be extra alert in Nepal (tobacco/areca users, alcohol, prior lesions, sun-exposed workers)

Certain habits and occupations elevate your risk substantially. You should be extra vigilant if you use any form of tobacco (smoking, chewing, or both), consume areca nut (supari) or betel quid (paan), drink alcohol regularly, or have a history of pre-cancerous lesions in your mouth. Studies across South Asia show that combined tobacco and areca use multiplies risk far beyond either habit alone.

Outdoor workers, farmers, construction laborers, traffic police, street vendors, face chronic sun exposure to the lips, which increases squamous cell carcinoma risk on the lower lip. Prior oral lesions such as leukoplakia, erythroplakia, or oral submucous fibrosis (discussed later) mark you as higher risk even after successful treatment. People with a family history of head and neck cancers or immune suppression from transplant medications or HIV also fall into the high-alert category.

Quick myth-buster: “only smokers get it” and common misconceptions

No, oral cancer does not only affect smokers. While tobacco is the single largest risk factor in Nepal, non-smokers who chew areca nut or paan are equally vulnerable. Human papillomavirus (Human Papillomavirus [HPV]), particularly type 16, causes a subset of oropharyngeal (throat) cancers even in people with no tobacco or alcohol history. Sun exposure alone can cause lip cancer. Some oral cancers arise in individuals with none of the classic risk factors, underscoring the importance of routine screening regardless of your habits.

Another common myth is that “oral cancer always shows up as a painful ulcer.” As explained earlier, early lesions are painless. A third misconception is that “only older men get it.” Women who chew tobacco or areca are at significant risk, and oral cancer incidence in younger adults (under 40) is rising globally, partly driven by HPV-related throat cancers.

The 2-minute self-check (and the “2–3 week rule”)

A quick self-check with good lighting can help you notice ulcers, patches, swelling, or areas that bleed easily. A practical rule is to take any sore, patch, or lump seriously if it doesn’t improve within 2–3 weeks. If something is changing, growing, or repeatedly returning in the same spot, that’s a strong reason to get examined.

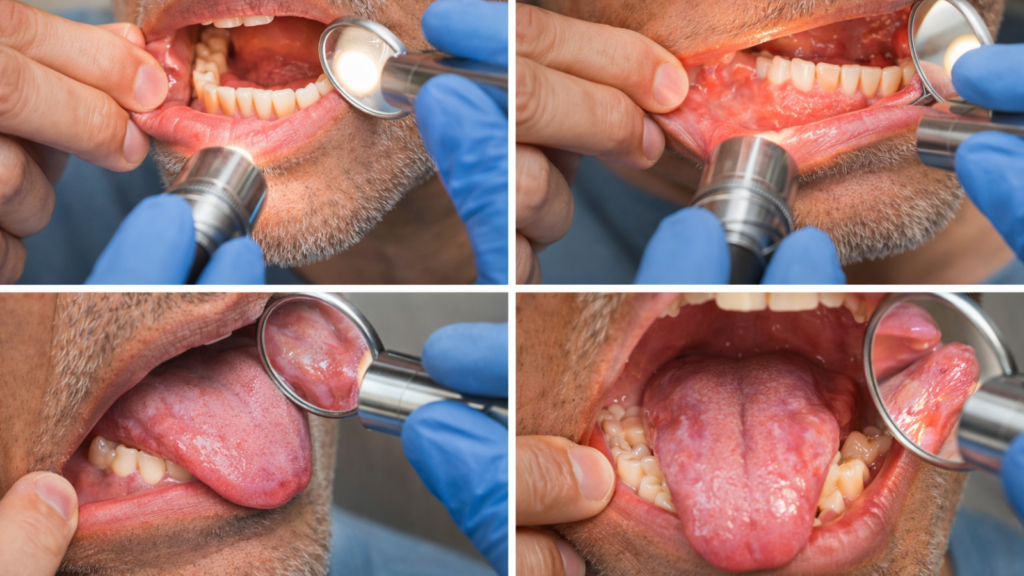

Step-by-step mirror exam: exactly where to look (sides/underside of tongue, cheeks, lips, gums)

Perform this exam once a month in good light using a small mirror and a flashlight or phone light. Stand in front of a bathroom mirror. Remove any dentures or removable appliances.

- Lips and outer mouth: Pull your lower lip down and inspect the inside surface for sores, lumps, or color changes. Repeat with the upper lip. Check the corners of your mouth (commissures) for cracking or white patches.

- Cheeks (buccal mucosa): Gently pull your cheek out to the side and look at the inner lining from front to back. Look for red patches, white patches, ulcers, or rough areas. Repeat on the other side.

- Gums and alveolar ridges: Lift your upper lip and examine the gum tissue around your upper teeth. Pull your lower lip down and check lower gums. Look behind the last molar on each side.

- Tongue (top and sides): Stick your tongue out and look at the top surface. Then stick it out to the left and inspect the right side edge; repeat to the right to see the left edge. These lateral (side) borders are high-risk zones.

- Underside of tongue and floor of mouth: Lift your tongue to the roof of your mouth and look at the underside and the floor beneath it. This area is frequently missed.

- Hard palate (roof of mouth): Tilt your head back and shine light up to see the roof. Look for lumps, ulcers, or color changes.

Feel each area gently with a clean finger to detect lumps, thickening, or firmness that looks normal but feels abnormal.

The “2–3 week rule”: any sore/ulcer/patch that doesn’t improve needs evaluation

Any ulcer, sore, or patch that persists for 2 to 3 weeks without improvement must be evaluated by a dentist or oral medicine specialist. Normal mouth sores (traumatic ulcers, minor aphthous ulcers) heal within 7 to 14 days. A sore that remains unchanged or grows after 3 weeks is abnormal.

This rule applies to white patches, red patches, mixed red-white lesions, lumps, and areas of roughness. Do not wait for pain or bleeding. The 2 to 3 week window gives your body time to heal minor trauma while catching genuinely suspicious lesions before they advance. Mark your calendar when you first notice the lesion; you schedule a screening if it is still present 3 weeks later.

Red/white/mixed patches: what to watch for (especially if persistent)

- White patches (leukoplakia) appear as non-removable white areas that cannot be rubbed off with gauze. They vary from thin, flat patches to thick, corrugated plaques. Most leukoplakia is benign, but 3 to 5 percent harbor early cancer or will progress to cancer over time.

- Red patches (erythroplakia) are flat, velvety red areas that do not rub off. Erythroplakia carries a much higher malignancy risk than leukoplakia, studies show that 30 to 50 percent of erythroplakia lesions contain cancer or severe dysplasia at the time of biopsy.

- Mixed red-white patches (speckled leukoplakia or erythroleukoplakia) combine both appearances and also carry elevated cancer risk. Any persistent patch, regardless of color, that does not resolve in 2 to 3 weeks warrants biopsy, not just observation.

Lumps, thickening, numbness, unexplained bleeding, or new “fit” problems with dentures

Lumps can be felt as firm masses under the surface, sometimes with normal overlying tissue. Thickening may present as a subtle bulge or a hardened area that feels different from the surrounding tissue. Numbness (paresthesia) or tingling in the lip, tongue, or chin without an obvious dental cause may signal nerve involvement by a tumor.

Unexplained bleeding, blood that appears without brushing trauma or gum disease, is a red flag. Denture wearers should note new fit problems: you suddenly find your denture loose, painful, or rubbing in a way it never did before because underlying tissue has changed. Do not simply have the denture adjusted; first have the tissue examined.

Symptoms you should not ignore (oral cavity vs throat differences)

Some warning signs are more urgent because they can suggest deeper involvement beyond the surface of the mouth. A neck lump, persistent hoarseness, one-sided throat pain, or pain when swallowing should not be “watched” for too long. Even if the mouth looks normal, symptoms in the throat area can still need evaluation.

Mouth (oral cavity) vs throat (oropharynx): why symptoms can look different

The oral cavity includes everything you can see when you open your mouth wide; the oropharynx (throat) sits behind the soft palate and includes the base of the tongue, tonsils, and throat walls. Oral cavity cancers produce visible lesions you can often see or feel. Oropharyngeal cancers are hidden and cause symptoms related to swallowing, breathing, or referred pain to the ear.

Oral cavity tumors may remain asymptomatic until they ulcerate or grow large. Oropharyngeal tumors, even small ones, can cause sore throat, painful swallowing (odynophagia), and voice changes because they sit near critical structures. HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers are more common in non-smokers and may present first as a neck lump from lymph node spread, with minimal visible mouth changes.

Urgent red flags: neck lump, one-sided swelling, or symptoms getting worse

A firm, painless lump in the neck that persists for more than 3 weeks is a critical warning sign. This lump often represents a metastatic lymph node and may be the first clue to a hidden oral or throat cancer. One-sided swelling of the tonsil, tongue base, or cheek, especially without infection or trauma, also demands urgent evaluation.

Symptoms that worsen over weeks rather than improve signal progression. You notice progressive difficulty opening your mouth (trismus), increasing pain, or worsening dysphagia (swallowing difficulty) and do not wait. These red flags require same-week screening, not “wait and see.”

Persistent sore throat, painful swallowing, ear pain, hoarseness/voice change

A sore throat lasting more than 3 weeks without fever or upper respiratory infection is abnormal. Painful swallowing (especially one-sided or worsening) suggests a lesion on the tonsil, tongue base, or pharyngeal wall. Referred ear pain (otalgia) occurs because the throat and ear share nerve pathways; you feel ear pain with no ear infection because a tumor in the throat irritates the nerve.

Hoarseness or voice change persisting beyond 2 weeks, especially in the absence of laryngitis or overuse, may indicate laryngeal involvement or a tumor pressing on the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Voice changes combined with difficulty swallowing or neck mass form a triad that requires immediate otolaryngology (ENT) referral.

When a “normal-looking mouth” still needs checking (HPV-related risk and throat-area symptoms)

You can have advanced oropharyngeal cancer with a completely normal-looking mouth. HPV-related cancers often arise deep in the tonsil crypts or tongue base. The only visible sign may be a neck lump or the only symptom may be persistent sore throat or ear pain. Traditional oral self-exam will not detect these.

You experience any of the symptoms in section 3.3 for more than 3 weeks and see a dentist or ENT specialist for a full examination, including fiberoptic inspection of the throat and base of tongue. Do not assume a normal-looking mouth rules out cancer.

High-risk conditions and habits

In Nepal and South Asia, areca/betel nut products (like paan or gutkha) are important risk factors and can cause precancerous changes over time. Conditions such as oral submucous fibrosis can show up as burning, stiffness, or reduced mouth opening, signs people often dismiss. Reducing exposure and getting regular checkups can significantly lower long-term risk.

Oral potentially malignant disorders (OPMDs): what they are and why dentists track them

Oral potentially malignant disorders (Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders [OPMDs]) are lesions or conditions that carry an increased risk of transforming into cancer. These include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucous fibrosis, oral lichen planus (certain forms), and actinic cheilitis. Not every OPMD will become cancer, but the risk is high enough to warrant regular monitoring and, in many cases, biopsy.

Dentists track OPMDs by recording location, size, appearance, and changes over time. You measure the lesion, photograph it, and schedule follow-up at 3 to 6 month intervals. Biopsy is indicated whenever the lesion enlarges, changes color, becomes symptomatic, or shows high-risk features (nodular texture, ulceration, mixed red-white appearance). Early intervention, including habit cessation and surgical removal of high-risk patches, reduces cancer incidence.

Leukoplakia and erythroplakia: when “just a patch” can be a warning sign

- Leukoplakia is a white patch that cannot be rubbed off and cannot be diagnosed as any other defined lesion (such as lichen planus or candidiasis). It most commonly appears on the buccal mucosa, tongue, and floor of mouth. Transformation rates vary: homogeneous (flat, uniform) leukoplakia has lower risk; non-homogeneous (nodular, speckled, or verrucous) leukoplakia has higher risk.

- Erythroplakia is a red, velvety patch. It is less common than leukoplakia but far more dangerous: studies show malignant transformation rates of 30 to 50 percent or more. You see a persistent red patch in your mouth and consider it a high-priority lesion requiring biopsy, not observation.

Both lesions are driven by chronic irritation (tobacco, areca, alcohol, sharp teeth, ill-fitting dentures). Removing the irritant sometimes causes regression, but biopsy remains the only way to rule out cancer or dysplasia. “Just a patch” can be early cancer.

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF/OSMF): burning mouth, stiff cheeks, reduced mouth opening

Oral submucous fibrosis (Oral Submucous Fibrosis [OSF or OSMF]) is a chronic, progressive condition caused primarily by areca nut (supari) chewing. It starts with a burning sensation in the mouth, especially when eating spicy foods. Over time, the oral mucosa becomes pale and fibrous; the cheeks, soft palate, and lips lose elasticity. You develop trismus (reduced mouth opening), difficulty swallowing, and inability to protrude the tongue normally.

OSF is classified as an OPMD because it carries a 7 to 13 percent malignant transformation rate over 10 to 15 years. The fibrosis creates a rigid, immobile tissue bed that is prone to chronic trauma and dysplastic change. Early-stage OSF may improve with areca cessation, oral physiotherapy (jaw exercises), and topical corticosteroids. Advanced OSF requires surgical release of fibrotic bands and long-term cancer surveillance. You chew areca or paan and notice burning or stiffness and stop the habit immediately and seek evaluation.

Risk reduction plan: quitting tobacco/areca, alcohol moderation, oral hygiene, nutrition, routine checkups

- Firstly, quit all forms of tobacco and areca nut use. Cessation reverses some precancerous changes and dramatically lowers future risk. Resources in Kathmandu include tobacco cessation clinics at major hospitals and community programs; nicotine replacement therapy (gum, patches) and behavioral counseling increase success rates.

- Secondly, moderate alcohol consumption. Heavy drinking (particularly spirits) synergizes with tobacco to increase risk. You limit intake to occasional social use or eliminate it entirely.

- Thirdly, maintain excellent oral hygiene: brush twice daily with fluoride toothpaste, floss daily, and have professional cleanings every 6 months. Chronic periodontal disease and poor hygiene contribute to inflammatory microenvironments that may promote carcinogenesis.

- Fourthly, eat a diet rich in fresh vegetables and fruits (sources of antioxidants and vitamins A, C, E) and minimize processed foods and red meat. Fifthly, schedule routine dental checkups every 6 months; dentists are trained to detect early oral cancer and OPMDs. Early detection through routine screening is the single most effective secondary prevention measure.

When to get a screening in Kathmandu: what happens and what’s next

An oral cancer screening is usually a careful visual exam of the mouth plus gentle palpation (feeling) of tissues and the neck to detect lumps or firmness. Screening helps identify suspicious areas, but it cannot confirm cancer on its own, biopsy is the definitive test when needed. If something looks abnormal, the next step may be a short review period, a biopsy, or referral to an oral surgeon/ENT depending on the risk level.

What an oral cancer screening includes: history, full mouth exam and feel of mouth/neck

A comprehensive oral cancer screening begins with a detailed health history. The dentist or specialist asks about tobacco, areca, and alcohol use; previous oral lesions; family history of cancer; symptoms (pain, numbness, bleeding, difficulty swallowing, voice change, ear pain, neck lumps); and duration of any current lesion.

The examination involves systematic visual inspection and palpation. The clinician examines all the surfaces described in section 2.1, using good lighting and sometimes magnification. Palpation (feeling with gloved hands) detects lumps, thickening, or firmness not visible to the eye. The neck is palpated bilaterally to check for enlarged lymph nodes, size, consistency, mobility, and tenderness are noted. The entire exam takes 5 to 10 minutes.

What screening can’t confirm (and why biopsy is the definitive step)

Screening identifies suspicious lesions but cannot confirm cancer. Visual and tactile examination can suggest malignancy based on appearance (ulceration, induration, fixation to underlying tissue, red or mixed patches), but definitive diagnosis requires histopathological examination of a tissue sample, a biopsy.

A biopsy involves removing a small piece of the lesion (incisional biopsy) or the entire lesion if small (excisional biopsy) under local anesthesia. The tissue is sent to a pathology lab where it is processed, stained, and examined under a microscope. The pathologist reports whether the tissue is normal, shows dysplasia (pre-cancer), or contains cancer, and grades the severity. Screening guides which lesions need biopsy; biopsy provides the diagnosis.

Adjunct tools (lights/dyes): when they help and their limitations

Adjunct screening devices use special lights or dyes to enhance visualization of abnormal tissue. Examples include toluidine blue staining (a dye that binds to dysplastic or malignant cells), autofluorescence imaging (tissue fluoresces differently under blue light when abnormal), and chemiluminescence (tissue appearance changes under special light after an acetic acid rinse).

These tools can help identify lesions that might be missed on visual exam alone or guide the clinician to the best biopsy site within a large lesion. However, they have limitations: they produce false positives (inflammation, trauma, and benign lesions can also light up or stain) and false negatives (some early cancers do not stain or fluoresce abnormally). Adjuncts supplement but do not replace clinical judgment and biopsy. Clinics in Kathmandu with advanced equipment may offer these aids; their use is optional and should not delay biopsy when clinical suspicion is high.

After an abnormal finding: re-check timeline vs biopsy vs referral (ENT/oral surgeon) and how to prepare

The clinician first assesses whether the lesion might be due to reversible trauma (sharp tooth, ill-fitting denture, cheek biting). You remove the irritant and re-examine in 2 weeks. The lesion resolves and it was traumatic; it persists or worsens and biopsy is scheduled.

Biopsy can be performed by an oral surgeon, an ENT specialist, or a trained dentist. The procedure is quick (15 to 30 minutes), done under local anesthesia, and may require a few stitches. Results typically return in 5 to 10 days. You prepare by continuing any medications (unless instructed otherwise), eating a light meal beforehand (to avoid fainting), and arranging transport home because numbness may affect speech and swallowing temporarily.

Referral to an ENT or oral-maxillofacial surgeon is indicated for: lesions in difficult-to-access areas (base of tongue, tonsil, pharynx), lesions requiring imaging (Computed Tomography [CT] or Magnetic Resonance Imaging [MRI]) to assess depth or spread, confirmed cancer requiring staging and multidisciplinary treatment planning, or when the primary dentist prefers specialist management.

You receive a cancer diagnosis and the team will discuss staging, treatment options (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, or combinations), prognosis, and supportive care. Major hospitals in Kathmandu with head and neck oncology services include Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, Bir Hospital, and private centers like Grande International Hospital and Norvic International Hospital.

Do not wait for pain to appear. Oral cancer in its earliest, most curable stage often causes no discomfort. Performing a monthly 2-minute self-check, knowing the 2 to 3 week rule, and seeking prompt evaluation for any persistent change can save your life. High-risk individuals, especially those using tobacco, areca, or alcohol, should schedule professional screenings every 6 months.

You notice a sore, patch, lump, or any of the red-flag symptoms described here and contact a dental clinic in Kathmandu immediately. Early detection transforms oral cancer from a life-threatening disease into a highly treatable one. Take control of your oral health today, your future self will thank you.

For professional oral cancer screening and comprehensive dental care in Putalisadak, contact BrightSmile Dental Clinic at +977-9748343015 or email brightsmileclinic33@gmail.com. Our team provides thorough examinations, transparent guidance, and immediate referral when needed, because catching it early makes all the difference.

What are the earliest signs of oral cancer?

The earliest signs of oral cancer include a mouth ulcer that doesn’t heal within 2–3 weeks, a persistent white or red patch, or a firm lump. Other signs include unexplained bleeding, numbness, or a rough patch that catches on teeth. Pain is often absent in early stages, so persistence signals concern.

How long should a mouth ulcer last before I worry?

A mouth ulcer should heal within 7–14 days. If it lasts more than 2–3 weeks or grows, bleeds, or feels firm, it needs evaluation. Persistent ulcers raise concern for serious conditions, so prompt assessment by a dentist or doctor is advised when healing is delayed.

Are white patches in the mouth always cancer?

White patches in the mouth are not always cancer. They can result from irritation, friction, cheek biting, or fungal infections. However, a white patch that doesn’t rub off or resolve after 2–3 weeks may be precancerous and needs a dental evaluation or biopsy.

What about red patches and are they more serious?

Red patches may result from irritation, but persistent red patches can be more serious than white ones. Lasting over 2–3 weeks or bleeding easily signals higher risk. Dentists treat persistent red lesions with urgency and may recommend biopsy or monitoring.

Can oral cancer be painless?

Yes, oral cancer can be painless in early stages. Because of this, people may delay seeking care. Visible changes that persist, such as lumps or patches, should still be examined, even without pain, since absence of pain doesn’t mean absence of danger.

Does smoking or chewing tobacco guarantee oral cancer?

Smoking or chewing tobacco does not guarantee oral cancer, but it significantly increases risk. The risk is even higher when combined with heavy alcohol use. Many users never develop cancer, but early screening is essential to detect silent changes.

Is areca/betel nut (paan/gutkha) dangerous even without tobacco?

Yes, areca or betel nut is dangerous even without tobacco. It is linked to oral submucous fibrosis, a precancerous condition. Users often feel burning, stiffness, or reduced mouth opening. Regular screening is important for anyone using these products.

What is oral submucous fibrosis and what does it feel like?

Oral submucous fibrosis is a condition where mouth tissues become stiff and less flexible. It causes burning with spicy food, tight cheeks, reduced mouth opening, and difficulty moving the tongue. It’s linked to areca nut use and increases oral cancer risk.

What happens during an oral cancer screening at a dental clinic?

During an oral cancer screening, a dentist examines the lips, tongue, cheeks, gums, and neck for unusual changes. They use light and palpation to detect lumps or firmness. The dentist also asks about habits like tobacco or alcohol use and may recommend biopsy if needed.

If something looks suspicious, does that mean I have cancer?

No, a suspicious lesion doesn’t mean you have cancer. Many lesions are benign. Screening helps identify what needs further testing. Only a biopsy can confirm cancer. Early checks often lead to simpler treatment, whether or not the lesion is malignant.